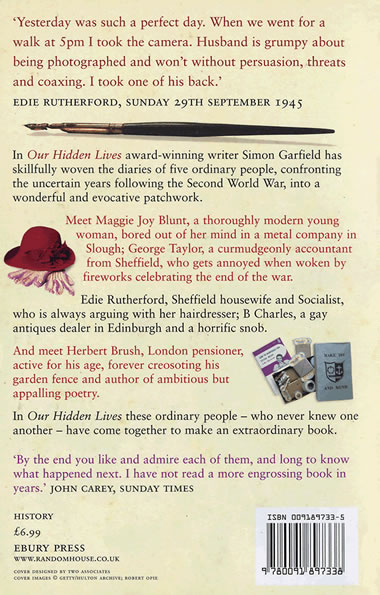

Our Hidden Lives

Our Hidden Lives

About The Book

I’d love to claim full credit for the birth and success of Our Hidden Lives, but I’d feel guilty and get sarcastic phonecalls. The book came about after an editor at Ebury Press/Random House made contact with the Mass Observation archive at the University of Sussex with the hope that there may be a good book to be made from all that wonderful material. The editor mentioned it to a colleague who knew of my interest in working with oral history and personal testimonies, and not long afterwards I found myself at the Falmer campus near Brighton with my jaw dropping open.

I first learnt about Mass Observation at school, but knew very little about it. I knew it was formed in the years before the Second World War, and that it contained accounts of ordinary people’s lives (people all over the country sent answers to questionnaires and copies of their diaries each month), but I had no idea about the range or detail of the material. I now know a little more.

In 1936, the anthropologist Tom Harrisson arrived back in England from the South Pacific, where he had been observing cannibals. Within weeks of his return he had arrived at a startling realisation: remote tribes were all very interesting, but they were not more interesting than the inhabitants of Bolton, where Harrisson lived. What was needed, he believed, was an ‘anthropology of ourselves’, a study of everyday people living regular lives. He reasoned that the press was not providing this service, and the government did not understand the most basic attitudes, desires and fears of those they served.

At about the same time, two other men were reaching similar conclusions. Charles Madge, a poet and journalist, and Humphrey Jennings, a documentary filmmaker, wrote a letter to the New Statesman describing their plans for a new type of scientific survey, one which would enable, for the first time, ordinary people to explain the detail of their days. The letter appeared in the same issue as the only published poem by Tom Harrisson, and in this way the concept of Mass-Observation was born. Notices appeared in newspapers and magazines asking for volunteers who would be willing to share their thoughts. More than 1,000 responded.

The methods of Harrisson and Madge/Jennings were very different. Harrisson employed a team of paid professional observers – journalists, social scientists, civil servants – to note down passing opinions and overheard conversations in pubs, factories and holiday resorts. Madge and Jennings sent out ‘directives’, questionnaires requiring ordered reactions to specific answers: what did they think of Chamberlain? Did they engage in any sporting activity? What were the advantages of having a royal family? New Observers were presented with a simple task to get them in the swing: ‘As a first test of your powers of observation, try the following: Write down in order from left to right all the objects on your mantelpiece, mentioning what is in the middle…’

By September 1939 the tone had changed. A ‘Crisis Directive’, printed in red ink, asked for specific reports on gas masks, masking windows and bomb-proof shelters, and also this: ‘Failing further directions being sent you, would you keep a diary for the next few weeks, keeping political discussion at a minimum, concentrating on the details of your everyday life, your own reactions and those of your family and others you meet.’ This was the first request for free-form monthly diaries, and about 500 people responded to the new challenge. They wrote from industrial centres, country towns and remote villages, completing their diaries after their work as secretaries, accountants, shopworkers, scientists, schoolteachers, civil servants, housewives and electricity board inspectors.

In all, an estimated million pages found their way to the Mass-Observation headquarters at Grotes Buildings, Blackheath. Some arrived on scraps of tissue, some on scented notepaper, some neatly typewritten, many almost illegible. Some people wrote three pages a month, some wrote 40. Some commented merely on the weather and their journey to work; some wrote predominantly about the contents of the newspapers; but some kept highly compelling and detailed journals containing almost every joy, disappointment and quirk of their lives. In many cases, married couples kept their writing secret from their partners, often recording their days late into the evening or before daybreak.

Mass-Observation’s small staff were swiftly overwhelmed by the flood of words they had released, and by the lucidity and diversity of its correspondents. After a few years the founders of the project squabbled over what use to put its assets and left for other work. New staff took over in an office in Bloomsbury, and they claimed to read every submission that arrived. But the diarists received little feedback, and in time came to wonder whether their work often lay undisturbed in the sealed envelopes in which they were sent.

The diaries are now lovingly archived in cardboard boxes at Sussex, where they are frequently examined by students and researchers concerned with the build-up and progression of the Second World War. Most diarists had stopped by 1945, but a few kept on writing as the country emerged to face momentous change and great challenges. The passage from war to peace is told in the simplest, most personal and moving terms, providing a singular window into the British temperament during one of the most under-examined periods of our recent history. Pure and direct, the impression that emerges from these writings is truly one of a vanished England, where a trip to the Charing Cross Road is a treasured event, and where a moment’s slight by a neighbour is likely to be remembered for years.

On my first visit it was hard to know where to start reading: there were tens of thousands of pages to sift through and many reels of microfiche. Inevitably I was drawn to the ones I could read easily, and to those who wrote well. The initial thought was to do something connected with the war, but then I wondered if it would be more interesting to start looking at the post-war material: there wasn’t so much of it, and the period was studied far less. Also, I knew relatively little about what happened between 1945-48, and I became hooked as soon as I read the first entries. The most striking thing was how often the diarists wrote ‘but I thought we had won the war…’. The austerity dragged on and on, the weather got worse and worse, the new Labour Government raised taxes and imposed restrictions unimagined even in wartime, and people wrote about it day-to-day as an intrepid British adventure…

The original plan was to have nine or ten diarists in the book, but it soon became clear that this would have entailed editing them to shreds. Eventually I chose five, and tried to tell the history of the period through them.

Fortunately, one can also read the book just as five highly engaging character studies. By the time I had whittled down my choice to those who were legible, those who wrote throughout the period and those who wrote more than just ‘I got up, went to work, went to bed,’ I was left with about thirty diarists to choose from, and I then selected what I believed to be the most interesting and engaging five. It was also important to get a combination of men and women with different ages, outlooks and locations.

My first thought was to run from VE Day in May 1945 to the Festival of Britain in 1951, the event long considered the watershed of a new modern Britain. But the diaries begin to peter out at the end of the 1940s (though a few Mass Observers wrote until the 1960s), and I reasoned that the birth of the NHS in 1948 – the pinnacle of Attlee’s reforms – might be a better place to stop. Also, it meant that the book would be a manageable length, and readers wouldn’t get hernias.

I like all five diarists in the book for different reasons. B Charles is a terrible snob and horrendously anti-Semitic, but his entries are compelling; Maggie Joy Blunt is an intense, astute and lyrical writer; Edie Rutherford’s displays of fortitude are inspiring; George Taylor’s buttoned-down world-view is curmudgeonly, proper and enquiring; and Herbert Brush is effortlessly and constantly amusing with his tireless creosoting, brave allotmenteering and furtive desire to eat sausage rolls in the National Gallery. Everyone who reads the book seems to find their own things to enjoy and abhor about all of them. The common link is that they are all sincere, and write without an eye on future publication. As such, their diaries are an invaluable, if incomplete guide to what life was really like at that time.

None of the diarists are around anymore, but if they were here today they’d probably be shocked at how cosseted and secure most of us are in our lives, and how far our standard of living has improved. They would be confused by the choices we have, and bemused by the technology. They would see how the NHS and social welfare reforms that were so novel in their diaries have became a cornerstone of our society. They probably would have been against the war in Iraq. Goodness knows what they would have made of email and mobile phones; I would have liked to have seen Herbert Brush tackle both of them.

I have often been asked whether I keep a diary myself. I don’t, mostly because I write for a living and in the evenings I prefer to do something else. Also, I think – probably mistakenly – that my daily emails are a sort of diary. In the past I believed that ‘no one would be interested in my humdrum life,’ a thought obviously negated by the existence of this website, but also another factor: in sixty years time a historian might find the humdrum details fascinating, just as we do now with the diaries in Our Hidden Lives.

In October 2005 there will be a BBC Four drama based on the book, directed by Michael Samuels, written by David Eldridge, and starring Richard Briers, Sarah Parish, Lesley Sharp and Ian McDiarmid.

The extract is from the beginning of the book, and introduces four out of the five diarists writing in May 1945 (B Charles only takes up his pen in November).

The audio extract begins where the text excerpt finishes, and is taken from the Random House recording produced by Stuart Owen and featuring Joan Walker as Edie Rutherford, Moir Leslie as Maggie Joy Blunt, and Jeffrey Perry as Herbert Brush.

For more information about Mass Observation, visit www.massobs.org.uk

Extract

This extract is taken from the beginning of the book, as four diarists prepare to make the transition from war to peace in May 1945.

1: OUR TROUBLES ARE ONLY JUST BEGINNING

‘God bless you all. This is your victory! It is the victory of the cause of freedom in every land. In all our long history we have never seen a greater day than this. Everyone, man or woman, has done their best. Everyone has tried. Neither the long years, nor the dangers, nor the fierce attacks of the enemy, have in any way weakened the independent resolve of the British nation. God bless you all.’

Winston Churchill from the balcony

Tuesday, 1 May 1945

Maggie Joy Blunt, freelance writer and publicity officer in metal factory, living in Burnham Beeches near Slough

Important hours, important as those days at the end of August in 1939 preceding the declaration of war. This is tension of a different kind, expectancy, preparations being made for a change in our way of living. But the tempo is slower. We wait, without anxiety, for the official announcement by Mr Churchill that is to herald two full days’ holiday and the beginning of another period of peace in Europe. We wait wondering if Hitler is dying or dead or will commit suicide or be captured and tried and shot, and what his henchman are doing and feeling.

All the women of my acquaintance have strongly disapproved today of the treatment of the bodies of Mussolini and his mistress. I heard one man in the sales department when he was told that the bodies had been hung up by the feet say glibly ‘Good thing too!’, But RW and myself and Lys and Miss M are shocked and disgusted. Spitting on the bodies, shooting at them, seems childish and barbarous, and such actions cannot bring the dead to life or repair damage, and is a poor sort of vengeance. What a state the world is in and what a poor outlook for the future.

I have worn myself out spring-cleaning the sitting room. All Sunday and yesterday at it – it now looks so brilliant and beautiful I’ll never dare live in it.

We had ice cream in canteen for lunch today – the first for two or is it three years?

George Taylor, accountant in Sheffield

I noticed that the flags which were flying on the Town Hall yesterday, presumably in preparation for peace, have been taken down. Apparently the officials were premature in their preparations.

Read the full extract .pdf format (117k)